This post was originally published on All Out Cricket on September 23rd, 2014.

Despite the perceived strides made by the women’s game to achieve something approaching equality with the men, Middlesex allrounder Izzy Westbury identifies areas where more – much more – can be done.

“I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king.”

Sunday September 7 marked the birthday of Queen Elizabeth 1st, who despite ruling magnificently in a 16th Century man’s world, had to apologise for the very fact of being a woman.

Fast-forward to the 21st Century and our modern world is trying hard to prove that we have developed into an egalitarian society. Last week, for instance, saw the Royal and Ancient Golf Club vote in favour of allowing women members for the first time in its 260-year history. Sport, once a symbol of male physical prowess, is an excellent measure of where the human race stands in the fight for equality.

Superficially women’s cricket paints a positive picture – Sky Sports gave us wall-to-wall coverage of the women’s T20s, the contracts have come, there are shiny cars, Charlotte Edwards’ face stares down at me from above the frozen peas on my weekly shop, and the BBC Test Match Special coverage boasted a number of very able female commentators throughout the summer.

Yet dig a little deeper and the cracks start to show. The ‘S-word’ lingers. In an age where we supposedly accept and understand that men and women are, wait for it, different, sexist attitudes are all too apparent.

Sarah Taylor: one of the world’s best keepers, regardless of genderSarah Taylor: one of the world’s best keepers, regardless of gender

Sarah Taylor, perhaps the world’s finest wicketkeeper, male or female, recently tweeted a perfectly justified technical criticism of India (men’s) keeper, MS Dhoni. A notable number of answering tweets criticised not Dhoni but Taylor – for even suggesting as a “lady cricketer” that she had the right to comment on her male counterpart. It’s easy to dismiss such reactions as belonging to testosterone-fuelled keyboard warriors hiding behind the cloak of online anonymity, but such views aren’t always confined to the internet.

Of course much progress is being made – ever-improving media coverage of the women’s game is doing much to change such attitudes, and the outlook is positive. Clare Connor revealed earlier this year that for the first time, instead of her chasing the broadcasters to cover some – or any – of England women’s games, Sky were on the phone to her before she’d had a chance to even mention the upcoming fixtures. The tables appear to be turning.

And yet despite this, there are lots of little things that continue to undermine women’s sport. While they may have big plans for the future, Sky covered none of the India tour this summer and there wasn’t even an internet stream for the Test match. Go online and the ECB Twitter account insists on referring to the women’s matches with the hashtag #EngWomen, instead of #EngvInd or #EngvSA as it would do for the men. Then there are the scheduling conflicts. As England posted an impressive total of 141 in their second T20 against South Africa, the major journalists were at Lord’s sipping champagne and listening to Ian Botham deliver the prestigious Cowdrey Lecture – too busy to notice the international up the road. More recently The Cricketer magazine showed us how much they pay attention to the women by congratulating “Laura Whitfield” [sic] on her match-winning knock against South Africa in the final T20.

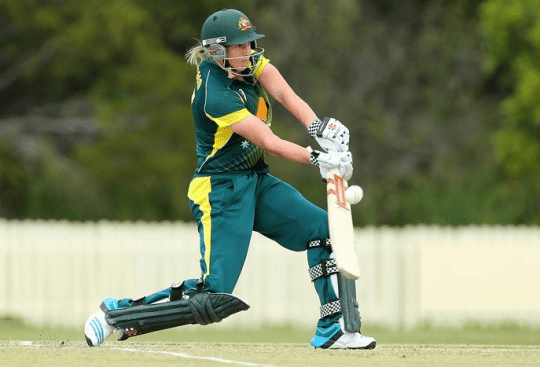

Elsewhere sexist attitudes are even worse. Down under, male ‘banter culture’ is pervasive, despite their having some of the most progressive infrastructure and funding for women’s cricket. Last year Ellyse Perry and Meg Lanning (pictured above), two of the world’s finest players, were subject to a patronising interview on the Cricket Show focusing almost entirely on the men’s team, their model shoots and condescending statements about the skill levels of women’s cricketers. This year it’s the furore surrounding the announcement that Lanning, the youngest person to ever score a century for Australia, male or female, has been added to the all-male Channel Nine commentary team. Social media is bemoaning her existence before she has spoken a word in her new role.

Clearly men’s cricket is often more exciting to watch in terms of being faster, more powerful, and so on – and if that is what dictates viewing figures then coverage should conform to this. However, there is much in the skill and style of women’s cricket that makes it as good, if not better, to watch than the men’s game. There are many other aspects that further complicate/explain the lack of coverage of women’s sport – entrenched attitudes, a developed men’s fanbase and short-term targets are all key factors. Give women’s cricket a chance and I have every confidence that it will create a sizeable and enthusiastic following of its own – it just needs a little push in the right direction.

So where does that push come from, other than the obvious call for increased coverage? For starters, pedantic fiddling with terminology isn’t the way forward. When female cricketers bat, we are ‘batsmen’. Batter? We’re not unisex ornaments. Bat? Really? Instead, we need to change how we view women’s cricketers. A higher profile brings an opportunity for the women to be judged not as girls having a run-around, or as weaker and feeble versions of the men, but as athletes in their own rights with their own virtues. Men will always be faster, stronger, bigger – it’s human physiology. But that doesn’t mean that women can’t have comparable skills, timing and strokeplay. Women should be judged by the same standards. As England vice-captain Heather Knight said earlier this summer, “We don’t want women’s cricket to be all soft and fluffy. If we don’t perform, we must be subject to the scrutiny. We want to be subject to praise when we do well and criticism when we don’t.”

Knocking sexism for six is about changing attitudes. Put a bat, ball, or microphone in our hands, and we’ll let that do the talking. Not only will women’s cricket be appreciated as a sport in its own right, but it will encourage more girls into the game. A bigger pool of players will raise standards even higher, and with that will come a larger audience. Then, instead of asking me which side I bat for (subtle), or whether I wear a box, ask instead what shot I’m working on or why I wouldn’t set that particular field, and let’s have a proper discussion – about cricket.