This post was originally published on 8th January 2014.

Australia is carving out a new identity for itself based uncannily on one we’ve seen before, led by a fragile moustachioed warrior who doesn’t do dull moments. Australian writer Geoff Lemon has witnessed at close-hand the return of pre-eminent pace to the epic Ashes story.

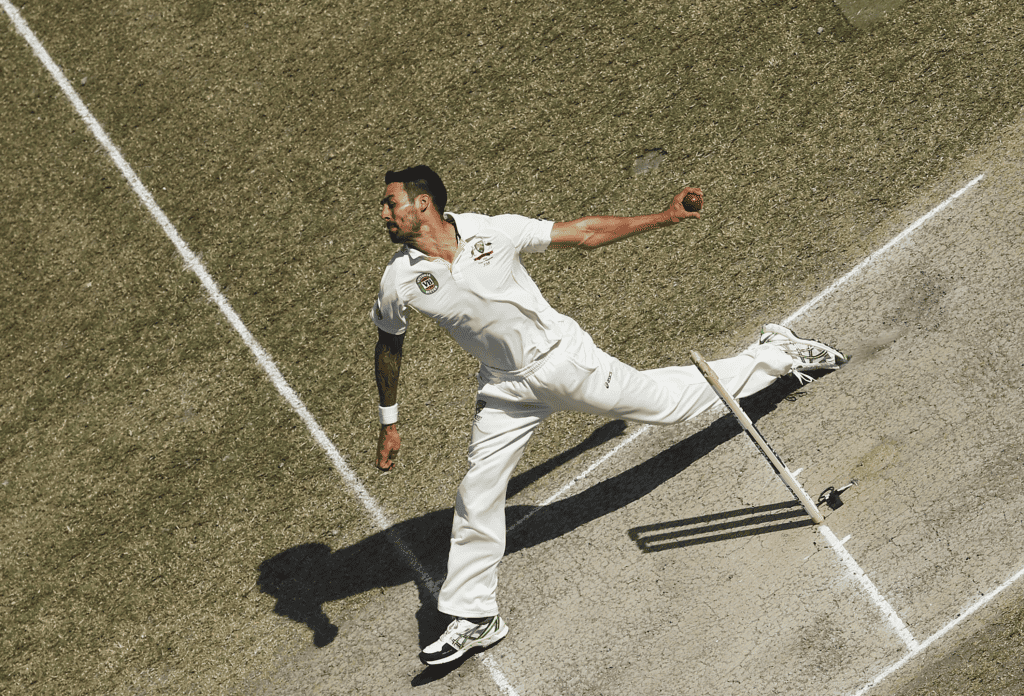

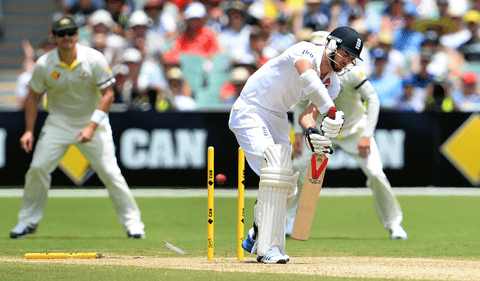

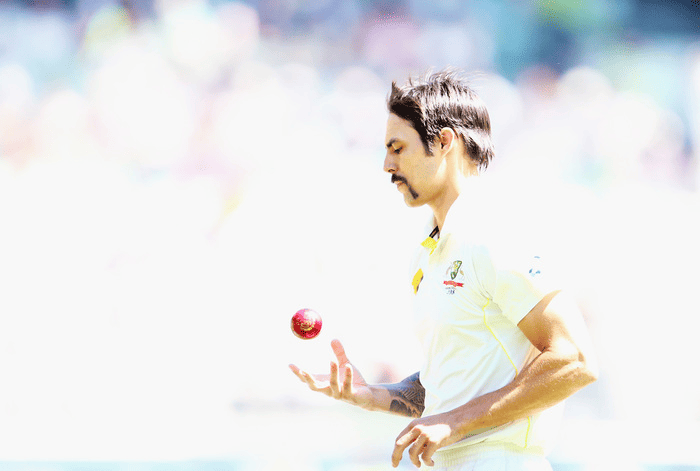

There is this moment, just before Mitchell Johnson will find himself on a hat-trick for the second time in half-an-hour, just after he has taken his fifth wicket of the innings. For the hat-trick ball the crowd will emit a rising distended roar, but for the one preceding it they are quiet. Four wickets have fallen in his last 17. Afternoon sun slants across his shoulders as he pauses, a natural lull like the space between heartbeats. It is a moment when concentration has not yet given over to delirium. They are fixed on him as he streams to the crease with that hunched springing run, ghosting his fingers over a ball that cuts in toward the left-handed James Anderson, carving past the stroke, destroying the middle stump’s camera in a carnival of timber.

This is the story of true pace and its pre-eminence. Cricket’s followers can list the game’s ornaments: pet shots by pet batsmen, quick feet down the pitch, supernatural spin, the power and innovation of the biggest hitters. But the simplicity of bowling fast, the kind of fast that needs no modifier, the kind around that triple-figure mile mark, draws a visceral response. It’s timeless, the most brutal attacker versus a solitary defence. It has become mandatory to award pace the appellation ‘raw’, with all those implications of something caustic, primal, unmeddled with. Of batsmen, perhaps Bradman and Sir Viv had the power to intimidate a team from one to 11. Shane Warne could sometimes reach that height with spin. But it is the common state of no one but the thunderbolt quick, this ability to dominate one side and lift the other through the sheer mechanism of power.

One half hour on the third day in Adelaide, and this Ashes becomes a throwback tour, both inside the ground and out. Suddenly a symbol of Australian machismo is celebrated and commercialised. Johnson is front and back of every newspaper. His moustache is debated on breakfast radio. It’s a consciously ironic nostalgia: the love for Merv and Boony is driven more by the comedy of facial hair than any on-field deed. Johnson is in fancy dress, apt given his new mode as a gruff enforcer is also an act. Glaring from his follow through, he is Tom to Joe Root’s Jerry. When he mimics the look on Ben Stokes’ face, he looks more than half cartoon.

We know it’s fake. A man whose career trademark is inconsistency, whose nerve has been known to fail under pressure, is held up as invincible. But there’s a deeper longing behind this. Australian cricket has been enduring an identity crisis, forced by several mediocre years into unfamiliar humility. There’s been an absence of identifiable heroes. Now, the passing of a fortnight offers the chance of renewed self-esteem. There is a craving to reach back to that fuzzy-chested medallion-wearing past, archaeologically excavating a caricature of Australian masculinity, only pausing to wipe off sweat with one finger. All the pub talk, according to writer and serial nostalgic John Harms, has been, “I haven’t seen an Australian bowl that quick since the ‘70s.”

The pairing of Lillee and Thomson is now treated less as history than mythology. Lillee wins the greater respect, but Thommo generates the awe. Bat and gloves at nose height, as Christian Ryan recorded it, but Thommo’s bowling “like a wave breaking, over the top it crashes.” The rawness – that word again – of character, approach, technique; the sense of an elemental force; the untestable nature of the claims about him. Others are accorded greater reverence, but Thomson at the peak of his powers is the transcendent Australian cricketer. He is the invocation of most potency. He is the comparison everyone gropes for instinctively through that afternoon and the days that follow, unable to comprehend a spell of such velocity without framing it in terms of 1975.

The story of the Ashes is the story of fast bowling. Frank Tyson perhaps the first athlete named for inclement weather. Demon Spofforth’s figures in the ninth ever Test match, still the second-best by an Australian. Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald: the former “a giant of superb physique” according to Cardus, while the “satanically destructive” McDonald produced “bowling of havoc but also of rare beauty”. There is Larwood punching Bill Woodfull in the heart, John Snow channelling the crowd barrage, even the conspicuous lack of a Test career for Eddie Gilbert, the Aboriginal bowler who Bradman declared the fastest he’d ever seen.

Johnson begins to write himself into this tradition not with his afternoon of carnage, but the previous evening. Alastair Cook’s day in the field has been long, hot and frustrating. He’s given 20 overs to bat before stumps. His feet are slow, a blankness in his eyes instead of the focus that has seen him through eight daddy hundreds and 17 baby ones. His listless prods outside off stump suggest a lookalike has been employed. When the coup de grace comes he hovers on the crease, boots in molasses, jabbing down a clear eight inches from the ball’s route to off stump.

A fast bowler’s signature is the bouncer: the peril, the mind game, the test of nerve, the clean spring of the ball so even the crowd at mid wicket can see the mode of attack. But his great achievement, his Mortal Kombat fatality move, is the batsman clean bowled. It is the resolution of cricket’s quintessential contest without recourse to outside assistance. Somehow all the catches in slips or the nicks behind seem like technicalities, things that sustain fast bowlers until the next time they see a stump spinning back, hear the thunk of a delivery that has swung or seamed or skidded to the point of that final sealing contact. “Stumps flying like spears,” as Cardus had it, the sight indicating the batsman’s most abject failure, the bowler’s fullest ascendancy.

Captain Cook is England’s long-innings man, the one who helped add 351 runs in one stretch last time he played on this ground. This time, he lasts nine balls from Johnson and doesn’t add a single run against him. His second innings will be better: that time he will find a run, before a counter-attack that betrays a frazzled mind. It is spurious to apply symbolism after the fact, but we all do. Given its manner, it is difficult not to see this first English wicket as the moment they are beaten.

Johnson was not supposed to be here. He was down on form for most of a year, out of the team for a year after that. He floated around, popped in for the odd cameo when back-up was required. A new generation of seamers proved more reliable. Included on the autumn tour as an India specialist, Johnson only played as an injury replacement in the final Test, where he was out twice for three runs and took no wickets as Australia lost inside three days. Left out of the touring party to England, his Test career was as good as done.

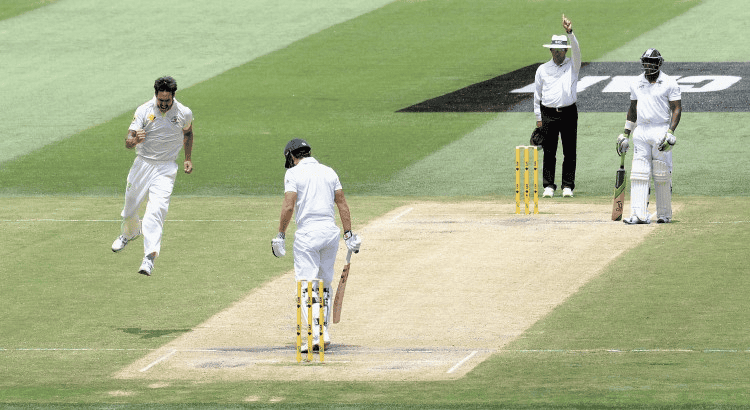

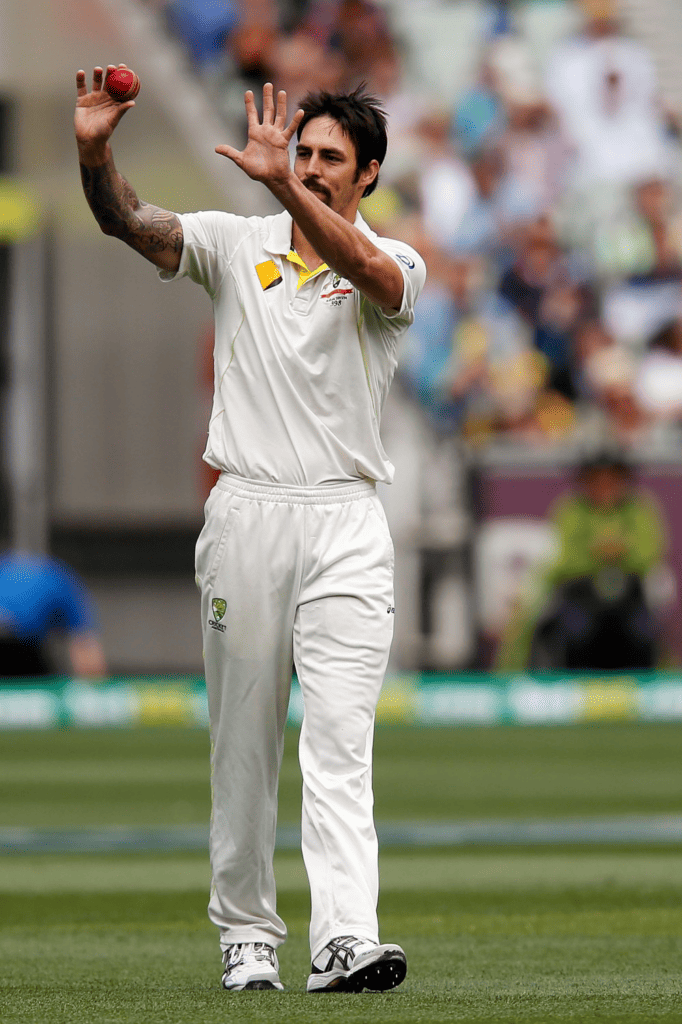

And yet. In the space of three overs on one afternoon, one of the most criticised cricketers in Australia’s history is forgiven. A triple-wicket maiden. Eight runs from the next. Two more wickets in the third. Two hat-trick balls, both fended in the air without going to hand. His nine wickets at Brisbane were good, spiteful balls bucking off a bouncy deck, but all of us have talked down the pitch at Adelaide as dead, slow, locked in for a draw. Visions of interminable English batting swim in our heads. Then there’s Johnson.

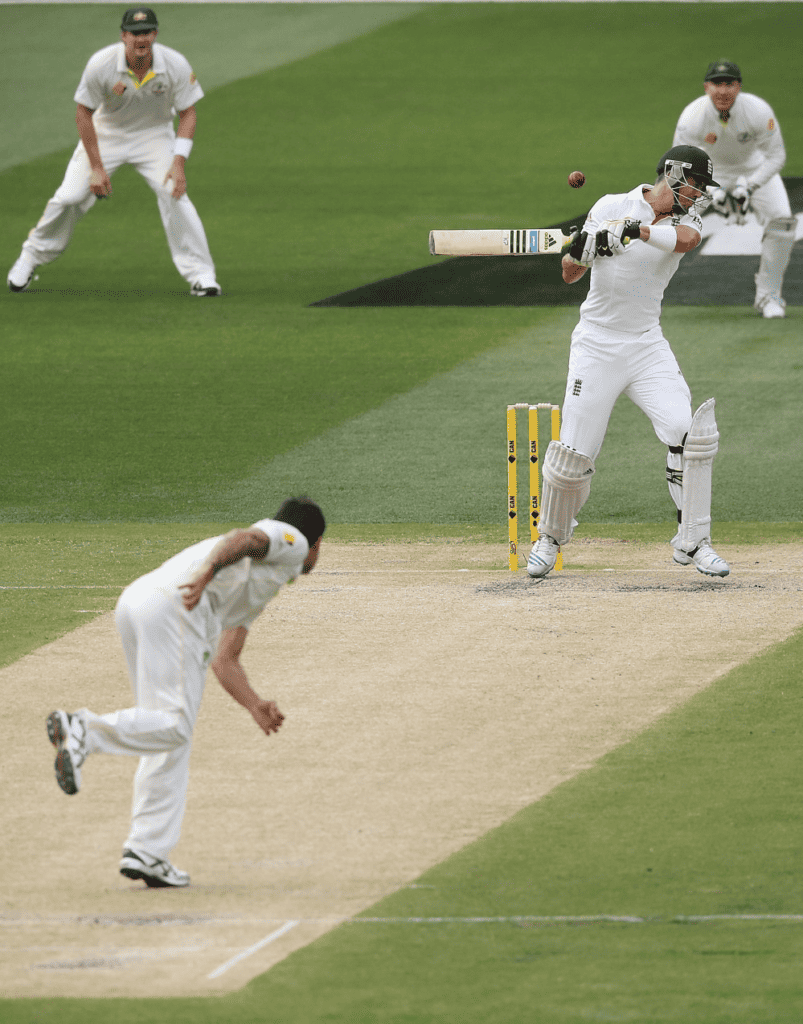

It’s not just the wickets, it’s the ferocity. He’s demolished England before, but that spell involved swing. Think back to Perth 2010 and I can still see the shape of the ball curving into the front pad of Trott, Pietersen, Collingwood. Today, it’s just speed as a guy slipping you a foil at a truck stop might describe it: pure, clean, does the job with a bang.

The ball is coming down faster than anything I’ve ever seen. From this docile track it’s lifting and humming into Brad Haddin’s gloves. Matt Prior gets a Woodfull ball to the chest, then one rears over his shoulder, making him twist away like an insect in a flame. The next tears past off stump, drawing the edge of a batsman in six minds and none at all. The press box is a hundred metres behind Stuart Broad, but the ball that rips through him makes some in the front row flinch. Graeme Swann is pure panic, Clarke bending back at slip like a Slinky. In the excitement, it is probably only the Anderson ball when everyone realises they’re watching one of the great Ashes spells.

Johnson has joined the pantheon. The power of pace compels them. Some will dispute this, saying it takes more than two good games to win such acclaim. But this isn’t about the man being ‘back’. Longevity is no requirement for pace bowling’s immortals. Tyson played 17 Tests, Spofforth 18. McDonald and Gregory played 11 together over less than a year. Nothing lasts forever, but the perfect peak of fury barely lives before decay. In a few games’ time, on a dead Colombo pitch, Johnson may be nothing. He may not care. A commenter named only as Matt writes on my article that day, “Frankly, I don’t care about consistency, the future or anything. If he destroys England here and in Perth, he can be whatever he likes for the rest of his career. He will have his name in history like Thommo, as a man who changed the Ashes.”

Thommo again. The most vital part of cricket is a real, proper, dirty quick. Pace simplifies the game, reducing the complex mechanics of skill and tactical planning to something with two moving parts, an atavistic contest based on velocity and the thrill of fear. These are uncertain times for cricket. The most explosive bowlers, those like Lasith Malinga and Shaun Tait, look to short matches. Fair enough. Why kill yourself with 30 overs a day?

But Johnson is here, in this series, shaking it till its teeth rattle. The emotive response, then, comes from seeing something timeless, out on the Test arena where it belongs: 4-61, 5-42, 7-40. When the third English innings of the tour ends, Johnson will have over half the wickets to fall. They’ll cost him less than nine runs each. He’ll have taken one every 20 balls, and in seven days of cricket will have all but regained the Ashes.

Adelaide, the dying ember of that third English innings. Johnson was taken off at nine wickets down, but returns for England’s last man. The travelling English fans don’t make a sound. I jot down a note. “He bowls to the left. He bowls to the right. Either way you’re f***ed.” It takes him two balls to rush through Monty Panesar.

Four times in this innings the stumps have gone down. Four of Johnson’s seven wickets have arrived with that sound, the explosion of movement as the bails scatter, the keeper almost levitating in delight. In cricket’s staid progression that flurry is like a single firework in a blank night sky, a frothing shoot of champagne at a Seventh Day Adventist funeral. Now Mitch is popping corks left and right and the congregation is getting sloshed. With arms round each other’s shoulders, they sway and announce in slurred tones that they never really say this, but they love you, man. In years to come they will remind each other they were here, attesting this with a fierce affirmation that says: I was part of something, I was real, in some small way I will never die.

The unidentified Matt is right. What happens next doesn’t matter. Mitchell Johnson may never take another Test wicket. But this moment is real, and when we look back, it’s this we’ll see. It’s this that creates the fervour rippling out from the Adelaide Oval on a sunny afternoon; 7-40 is the final number, but the real moment is that five-wicket spell. It’s that frantic patch of sheer destruction. It’s preparing to bowl to Anderson, the long pause, the crowd quiet, the moustache bristling, the arms beginning to pump. As that ball comes in, carving past the inside edge, beating the pad, lifting the middle stump out of the ground to leave the other two beaming a gap-toothed grin, Johnson is telling young fast bowlers, we can still rule the world.