This article was originally published on All Out Cricket on April 14th, 2015.

Richard H Thomas celebrates some gold medal performances, particularly the 1975 World Cup final effort from Gary Gilmour.

In the final of CWC 2015, there were several in the frame for the gold medal. Eventually Faulkner got it for his killer over, but it easily might have been his captain for a last one-day flourish, or Grant Elliott for singlehandedly setting a target beyond 100. In this case, the Man of the Match was a line-ball decision; it if was a stumping, the third umpire might have wanted numerous replays. There have been other times though, when the choice of standout performance has been less easy to predict; in some cases indeed, it has been incomprehensible.

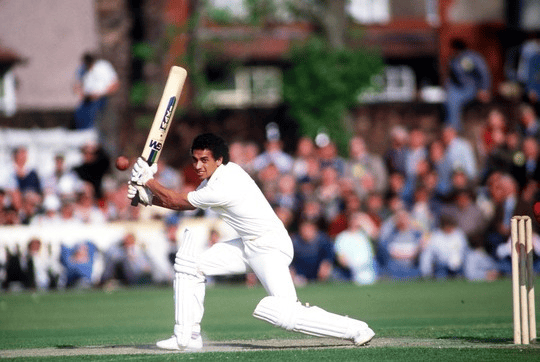

The most glorious example of unfathomable gong-giving came in Lancashire’s Benson and Hedges Cup Final win in 1984. Bowling first on a treacherous Lord’s morning, Paul Allott and Steve Jefferies destroyed Warwickshire’s batting, save for a masterful 70 from Alvin Kallicharan without which 139 all out would have looked even more miserable. After one or two alarms, arch-finishers David Hughes and Neil Fairbrother chased it down with a solid unbeaten 30-odd apiece. No astonishing performances then, but worthy contenders nonetheless. Everyone therefore was astonished, including the man himself who was seen to incredulously mouth the words “What-Me?” when Peter May chose Lancashire captain John Abrahams as his Man of the Match. He did, it must be said, collect and parade the trophy perfectly, but besides that he’d had the sort of day from which many club cricketers might have sulked silently home without showering. True, he’d caught Kallicharan, but otherwise he’d dropped a sitter, hadn’t bowled and his third ball duck had left his team with more of a struggle than the modest target merited. As reported on these pages previously, the combination of winning the toss and sticking them in was “clearly a triumph of such Churchillian magnitude over and above any such vulgar act as someone actually doing something”.

Often though, the Man of the Match is self-evident and doesn’t test the adjudicator’s mettle. In the 1965 Gillette Cup final for example, it was a no-brainer. Batting first, Yorkshire began soberly but then cut loose, and “as startling as anything about Yorkshire’s performance” wrote John Woodcock, “was that it was Boycott that led the way”. For “led the way”, read “went berserk”; 15 fours and three sixes was a full season of mayhem in normal Boycott terms; it was “a hell of an innings” said Brian Close. A target of 317 was ridiculous in 1965; the Tykes took the cup and adjudicator Doug Insole was the least stressed man in the ground. Even then, adulation for Boycott was tempered; “it is quite likely that Boycott will open England for a decade to come” continued Woodcock, “but the prospect of his doing so in his ascetic mood is hard to entertain”. The Times don’t make you Cricket Correspondent for nothing.

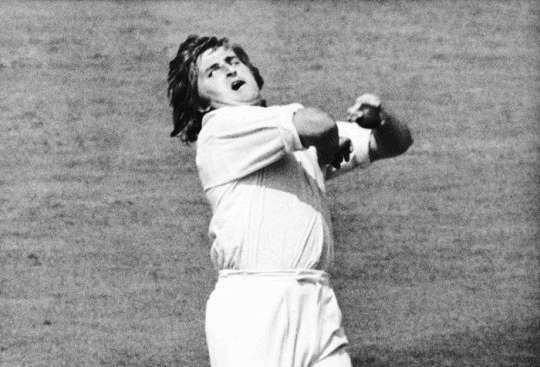

An even easier gold medal decision followed the World Cup semi-final at Leeds in 1975. An English-hosted tournament meant that undeveloped one-day skills and strategies met early season wickets and weather. The hosts were buoyed by some decent form, enthusiastic support and rather eccentric tactics from their opponents (Gavaskar took 60 overs over 36*). In the semi-final they met Australia. With little one-day experience and under the unyielding stewardship of Ian Chappell, they approached the task as they approached everything else; take no prisoners and be hard to beat. The conventional wisdom that England would be better prepared on an early season green top was soon disproved when they were fired out for 93 by a barrel-chested New South Walian called Gary Gilmour.

Wisden reported that the visitors moved swiftly about their business to get through their overs “before the greenness went” and to avoid batting “in the faint light of late evening”. Bowling left-arm seamers over the wicket, Gilmour took 6-14 – still the fifth-best World Cup figures. Spectators bemoaning the lack of value with the home side back in the hutch for less than 100 and the ball crossing the boundary only six times perked up when the visitors found themselves at 39-6. Enter Gilmour, whose run-a-ball 28* saw his team home. “The huge crowd rose to him,” reports Wisden, adding with delicious restraint that “former West Indies captain, Jeffery Stollmeyer had no difficulty in naming him Man of the Match”. Over 30 years later, and using 10 different sets of metrics, the Almanack rated it the greatest ever one-day bowling performance.

Gilmour was no one-hit wonder. In the final, and on a flat track at Lord’s in the blazing sunshine, his 5-48 included a handy West Indian middle order consisting of Kallicharan, Lloyd, Kanhai and Richards. Those watching would have hardly credited that they’d seen the best, and almost the last of Gary Gilmour. True, a year or two later he gave Richard Hadlee a fearful mauling on the way to a Test hundred, but his cricketing traction was scuppered by World Series Cricket. He played in 15 Tests, and appeared in only one more ODI after the Lord’s final. That his career was so unfulfilled suggested his Daily Telegraph obituary in 2014, “had much to do with a carefree, high-living approach both to the game and, indeed, to his life” including “a disinclination to buckle down to the kind of fitness demands that were becoming prevalent”. His own reflections were that “we played for fun rather than money”; an unfortunate truism which meant that when Gilmour needed a liver transplant in 2005, Ian Chappell led the fundraising campaign.

Gilmour’s career was one of “sporadic brilliance” suggested Jack Pollard, but in 500 more ODIs he would never have made such an impact. In the meantime, England’s batsmen might do well to remember that exactly 40 years ago they were undone in overcast conditions by an Aussie left-arm paceman. They’re bringing two this time. Roll on the summer.